![]() TOM MORGAN

TOM MORGAN

![]()

This article was begun on January 31st, 1996, at just before 9.00 p.m. At around that time and on that date eighty years before, two German airships were flying South over Shropshire, and although they didn't know it, they would soon bomb my town, and almost kill my great grandfather, my grandmother and her sister.

On January 31st, 1916, nine airships left their bases, an unusually large number, intending to make a statement about the Germans' ability to raid the United Kingdom. This time they would not creep across the North Sea under cover of darkness to haphazardly bomb the South coast of England and slink back home. This time their orders were to fly across the entire breadth of England en masse and bomb Liverpool which, until then, had been considered well beyond the range of the raiders.

The unprecedented scale and audacity of this raid would show the British a thing or two. It would make them realise that nowhere was safe from aerial attack. No longer could anyone say they were out of reach. Even distant Liverpool had become, to use a phrase which would become commonplace in later wars, a legitimate target.

Kapitšnleutnant Max Dietrich, commanding the L 21, was the first to cross the North Sea, passing over the Norfolk coast at 5.50 p.m. To the West he and his men could see a clear sunset, promising good weather. Inland, though, mists and fogs were already forming around the heavily-populated areas, making ground observation difficult. Not far away, in the fading light, Dietrich could see L13, commanded by the legendary Kapitšnleutnant Heinrich Mathy. who had already bombed London itself in the previous year. At height, and above clouds, it began to get very cold.

Dietrich, using a combination of calculation and observation whenever the clouds provided a gap through which he could see, plotted his progress across the country. Increasing his speed and leaving Mathy and the L13 behind, he saw the lights of a city below him. A calculation measuring airspeed against time told him that this was Manchester. He saw likely targets but decided not to drop any bombs, saving them and the surprise they would cause, for Liverpool.

At 8.50 p.m., looking down from the gondola, Dietrich could no longer see any lights or ground features at all and concluded that he was out over the Irish Sea, slightly to the North of Liverpool. He turned South, flying down the coast, looking for his target. Shortly afterwards, he saw it. There, twinkling below, below were the lights of a large town. Towards the South, separated by an area of darkness, was another, smaller town. Dietrich concluded that he was over Birkenhead and the larger Liverpool, separated by the wide mouth of the River Mersey. He ordered action stations and began his approach.

He steered out to sea and came in to attack from the South, intending to fly over Birkenhead, crossing the Mersey and so on to Liverpool itself. The officers stared at their instruments, calculating airspeed and altitude. The incendiary and high-explosive bombs were readied for release. There was a businesslike attitude aboard the airship. There had been no attempt at all to interfere with their progress across Britain. They had the skies all to themselves. Now they had reached their target the cold and boredom of their long flight were forgotten.

At 9.00 p.m. on 31st January, 1916, the people of Liverpool who were out and about - and there must have been many on that Monday evening, heard no droning engines to make them look upwards. Any who did look up anyway, saw no threatening, silvery cigar-shaped airship about to bomb them. In the streets of Liverpool that night, no fat, frock-coated, top-hatted merchants trod women and children underfoot as they rushed to save themselves, as German posters had depicted. There was no fear. There was no panic. There was no danger. Above all, there was no Zeppelin. L21 was nowhere near Liverpool, because Dietrich's calculations had been wrong.

When he thought he had passed over Manchester, he had been wrong. It was Derby which passed below the misty panes of the observation-window. When he thought he had crossed the coast and passed on over the Irish Sea, he had been wrong. He had been flying over the sparsely-populated and unlit areas of North Shropshire and Eastern Wales. When he thought he had flown over Liverpool and Birkenhead and the Mersey, he had been wrong. When Dietrich had located his target, called action stations and ordered his men to prepare to bomb, he had been wrong. He was not over Liverpool. He was 75 miles to the South-East. His "Birkenhead" was Tipton, a small industrial town in the middle of the Industrial West Midlands. His dark, featureless Mersey was an area of industrial wasteland and collieries known as Lea Brook. And his jewel, his "Liverpool" was Wednesbury - my town.

Dietrich's bombing run began. Bombs fell on Tipton and Bradley and then the first bombs fell on Wednesbury. They landed in the King Street area, near to a large factory. A woman, Mrs. Smith, of 14, King Street, left her house to see what the noise was. A little way down the street she saw fires and presumed an explosion at the factory. She walked towards the fires but bombs began to fall behind her. She turned and hurried home, to find her house demolished and all her family killed. The bodies of three members of her family - her husband Joseph, daughter Nellie aged 13 and son Thomas, 11, were quickly located. The youngest girl Ina, just seven, was lying dead on the roof of the factory. Her body would not be found until the morning. The first Wednesbury deaths had occurred. Above, L21 hovered, barely moving for the moment.

| The audience at the King's Music Hall in Earp Street had just settled down for the second half of the melodrama, "The Faithful Wedding" and Florence Hill and her sister Ellen were seated one each side of their father, in the stalls. As the house-lights dimmed they felt, rather than heard, some dull thuds. Shortly afterwards there were more and this time there was no doubt but that they were explosions, coming from somewhere nearby. As Florence, herself a munitions worker, began to think that there must have been some serious accident at one of the shell-filling shops during the evening shift, the theatre was plunged into darkness. There were screams and curses as the audience made for the direction of the doors in the inky blackness. Florence lost touch with her father and sister and joined the general movement towards the right of the auditorium, where the exit doors were, asking "Is that you, Dad?" whenever she fell over anyone and was helped to her feet. There was very little real panic, more a profound sense of inconvenience. |

|

There had been no more explosions but something had obviously happened outside and, whatever it was, it had fractured the gas-supply and cut off the lighting. Before long, Florence got outside and found herself not too far from Ellen. The girls looked for their father but in that crowd of angry and bewildered people he was nowhere to be seen.

The streetlights were out, and yet there was light from another source, somewhere over beyond the far side of the building along whose side wall the audience emerged. The light was glowing, red. They moved out into the street and saw the Zeppelin. There it was, high above the burning Crown Tube Works at the end of Union Street, its silvery envelope reflecting the flames which its bombs had caused. It must have looked like some giant dragon, hovering over its stricken prey. They heard the engines begin to race and saw the machine swing towards them.

They began to run up the hill towards the church, at the town's highest point, joining a throng of others who had found themselves obliged to stumble out into the dark to see what was happening, together with some of the customers of the many public houses near the town centre. A householder ran out and opened the heavy doors to his cellar, which normally formed part of the pavement. "Down here, quick!" he shouted, and many took him up on his offer. Others stayed out in the open to watch the Zeppelin.

Dietrich had already bombed Tipton, dropping incendiary and high-explosive bombs. In Union Street, two houses had been completely demolished and others damaged and the gas main had been set alight. In all fourteen people were killed in Tipton. Thomas Morris told later how he had gone to the Tivoli cinema. His wife had taken their children to visit her mother. When he reached his mother-in-law's house in Union Street he found that it was one of those demolished and among the rubble he found five bodies - those of his wife, two of his children and his wife's parents.

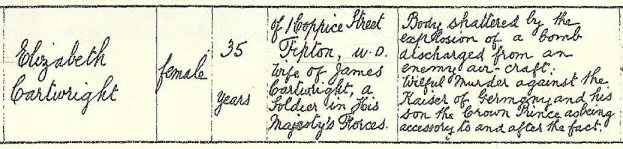

Incidentally, I am grateful to Colin Grainger for telling me about one of the Tipton victims, Elizabeth Insull. She had married James Cartwight, a boatman, on 30th January 1904 and was killed 12 years and a day later, when the raiders bombed Union Street, Tipton. Whoever was responsible for stating the cause of death did not mince his words when completing the Death Certificate a few days after the raid:

L21 had flown next over Lower Bradley, dropping five high-explosive bombs and killing a young courting-couple, Maud and William Fellows who, although they shared the same surname, were not related, whose deaths are commemorated by a small plaque on the wall near which they were standing when they died.

After leaving Wednesbury, flying the L21 almost over the heads of Florence, Ellen and the others watching from Church Hill, Dietrich headed North for Walsall. The first bomb there landed on a Congregational church. A preparation class of children from a local primary school was meeting in the church but no-one was injured, although a man walking by outside died instantly, the top of his head having been removed by debris or blast. Dietrich flew over the centre of Walsall and his last bomb wounded Julia Slater, the town's mayoress, as she rode on a tram. (She suffered severe wounds to the chest and abdomen and died a few weeks later, of shock and septicaemia. The Walsall Town war memorial now stands on the spot where this, Dietrich's final bomb, fell.) At Dietrich's command, the helmsman turned L21's nose towards home, and after a flight lasting 23 hours and 45 minutes, the ship landed at its base in Nordholz.

|

By now, Florence and Ellen Hill had decided to walk towards their

house and see if they could see their father. The Zeppelin had been out of

sight for some time, and it was getting very cold. They left Church Hill,

got home at about 11.00 p.m. and joined several neighbours standing in their

doorways, discussing the events of the night. After some twenty minutes,

Florence saw a man limping along the house-fronts, towards them. It was her

father.

Fearing that he had been hurt, everyone, neighbours and family alike, rushed to him. He was wearing only one boot. He had thrown the other one at L21 as it passed over him, and lost it. Following this act of impotent bravado, he had limped here and there, looking for his daughters until, exhausted, he had decided to go home, hoping to find them there. |

By midnight, the whole family was asleep. There had been much to think about. That night, they had all been in danger of sudden death, a danger as real and indiscriminate as that faced by Richard and Martin, the fiances of Florence and Ellen, currently "out there" in the trenches. The girls had read about Zeppelins in the newspapers, and now they had heard and seen one! Florence fell asleep thinking of Richard, out in France. And, she told me many years later, she thought of me, because she remembered thinking something along the lines of, "It'll be something to tell my grandchildren."

What she never thought of, though, as she fell asleep, was the possibility that in less than a quarter of an hour, she would be woken by a droning noise, would get out of bed and draw the curtains aside, and would see another Zeppelin bombing Wednesbury.

About three miles to the South, L19 wallowed in the sky, engines on tickover, while Kapitšnleutnant Loewe consulted his maps. Loewe had not been in contact with Dietrich in L21, but appears to have drawn the same mistaken conclusions as he flew over England. Even now, while Dietrich and his men were engaged on their reflective journey home, Loewe considered the evidence presented to him. Finally, his mind made up, Loewe gave his orders. Loewe had followed a similar course to that which Dietrich had followed. He, too, believed he had located Liverpool. Below him, he could see fires, still burning, convincing him that he had at last reached his target. As Florence slept, Commander Loewe gave his orders.

Wednesbury was in for it again.

L19 was a new ship, which had been commissioned at the end of November, 1915. Her engines had been giving trouble throughout the flight and thus it was that Loewe had fallen so far behind Dietrich in L21. (L21 was, in fact even younger than L19, having been handed over for service only around three weeks before the raid. Both ships had the same type of engine, yet those on L21 had performed well.)

Loewe dropped his bombs in the same area as Dietrich, several falling on Wednesbury. This second raider caused only minor damage and there were no casualties. Because of the lateness of the hour, there were few witnesses and Loewe's attack caused less of a sensation than Dietrich's. L19 began to weave slowly eastwards, heading for the coast. For Loewe, for his crew and for L19, this would be the last flight. The engine difficulties persisted and L19 came down in the North Sea. The floating wreck was spotted by a British steam trawler , the "King Stephen," whose captain, after speaking to the crew of the airship, refused to take them on board, fearing (as he said later) that they might overpower him and his men and force them to sail to a German port. The trawler sailed off looking for a Royal Navy Vessel, but by the time it reached port, the L19 had sunk. There were no survivors, although some crewmen sealed final messages in bottles and threw them into the sea, to be found some months later. One of the messages came from Loewe himself:-

"With 15 men on the top platform and backbone girder of the L19, floating without gondolas in approximately 3 degrees East longitude, I am attempting to send a last report. Engine trouble three times repeated, a light head wind on the return journey delayed our return and, in the mist, carried us over Holland where I was received with heavy rifle-fire. The ship became heavy and simultaneously three engines failed.February 2nd., towards 1 p.m., will apparently be our last hour.

Loewe."

Dietrich and L21, with all the other machines which had begun the raid (and whose exploits fall outside the scope of this present piece) returned home safely, to raid again. L21's link with Wednesbury ended on November 28th., 1916, when she was shot down in flames off the coast of Lowestoft after a raid on England. There were no survivors. The Commander at that time was Oberleutnant Frankenberg.

Nationally, the raid was seen as very embarrassing. Nine Zeppelins had been able to fly over England at will, with no interference. Several aircraft took off but none of them came anywhere near any of the airships. Much attention was given to Britain's air defences after that.

The raid on Wednesbury and the nearby towns was covered in the next evening's newspapers. There were photographs but due to censorship, no towns were named in the report. It made no difference. Everyone in Wednesbury knew what had happened, and where.

Today, hardly anyone does. The burnt-out shell of the Crown Tube Works, which remained untouched after the war, was demolished in the 1960s. The cast-iron lamp standards in King Street, peppered with shrapnel holes, were replaced at about the same time. The simple little wooden memorial which used to be seen fixed to a wall in King Street, bearing the names of those killed, disappeared many years ago, when the houses in King Street were demolished. Just one section of wall remains, its elderly bricks still bearing the scars of a bomb which fell nearby.

Florence Hill, my Grandmother, who had a grandstand view of the raid from Church Hill, died in 1994, aged 100 years. I know several people still living who were small children that night, when they saw the Zeppelins. The youngest of these is now 87 years old. The newspaper which reported the raids in 1916 is still published daily. There was no comment this time around.

UPDATE - 2003

Towards the end of 2003 I was invited to take part in a short BBC Television programme about the raid. This gave me the idea of trying to locate the graves of the Wednesbury victims. I knew that there had been a public collection to pay for the funerals, and that the dead would probably have been buried in the local cemetery. I visited the cemetery and looked at the part which contains the 1916 burials but there was no sign of any graves which mentioned the raid. I felt sure that any grave-markers paid for by public subscription would refer to the event, but - no luck.

Next, I visited the Local Authority's Cemetery Department to ask if records of burials still existed and to my surprise, they do. I was given a large ledger which contained (in beautiful copperplate handwriting) the records of all the burials in Wood Green Cemetery, Wednesbury, for the first few years of the 20th Century. I already knew the names I was looking for and they they all were, neatly bracketed together by the clerk, with the note "Zeppelin." Three of them were buried on November 5th, nine on the 7th, and one on the 9th. The locations of the graves was also given. Two days later, a member of the Department met me at Wood Green Cemetery and using his plans, we were able to locate the site of the now-unmarked graves. 13 graves take up a considerable space in the cemetery, but there is nothing to see today. The Zeppelin victims lie in one anonymous section of a large grassed area. Not far away are the graves of some Great War soldiers who died of wounds. Of course, these men have Commonwealth War Graves Commission gravestones which are carefully tended. The 13 Zeppelin victims - also victims of the war - have no memorial at all, apart from this one here:

January 31st, 1916

Mary Ann Lee, aged 59

Rachel Higgs, aged 36

Frank Thompson Linney, aged 36

Susan Howells, aged 30

Matilda Mary Burt, aged 10*

Joseph Horton Smith, aged 37

Ina Smith, aged 7

Nellie Smith, aged 13

Thomas Horton Smith, aged 11

Mary Emma Evans, aged 57

Edward Shilton, aged 33

Betsy Shilton, aged 39

Albert Gordon Madeley, aged 21

*Matilda's name is spelled BURT in the cemetery Register but BIRT on her death certificate.

UPDATE - 2012

| In November 2012 a new memorial appeared in

Wood Green Cemetery, commemorating the victims of the Zeppelin

raid. There was no prior announcement of the placing of

the memorial in the cemetery and at the time of writing (December 4th) no-one

knows who provided it. No doubt the identity of the donor will become

known in due course.

If so, I will provide a further update here. |

|

For a direct link to the author of this article, email Tom Morgan

![]()

Copyright © Tom Morgan, January,

1996.

Copyright © Tom Morgan, January,

1996.

Return to the Hellfire Corner Contents Section